Background:

In 1807, following his victory at the Battle of Friedland, Napoleon Bonaparte met Russian Emperor Alexander I at Tilsit, a town in modern-day Russia. On July 7th, the two emperors signed the Treaty of Tilsit, committing to a Franco-Russian alliance. This alliance proved transient: over the next five years, Franco-Russian relations cooled dramatically due to Napoleon’s creation of the Duchy of Warsaw;1 his failed marriage proposal to Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna; the annexation of the Duchy of Oldenburg;2 and fallout over Napoleon’s Continental System, which essentially barred trade with Great Britain. The last of these proved particularly significant, as the Continental System was unpopular in Russia and economically ruinous. Between 1807 and 1812, it led to a 1300 percent increase in Russian national debt, a 50 percent drop in the value of its paper currency, and a 40 percent drop in exports.3 As a result, Russia began violating the system and resumed trade with Great Britain; Napoleon was incensed by this betrayal.

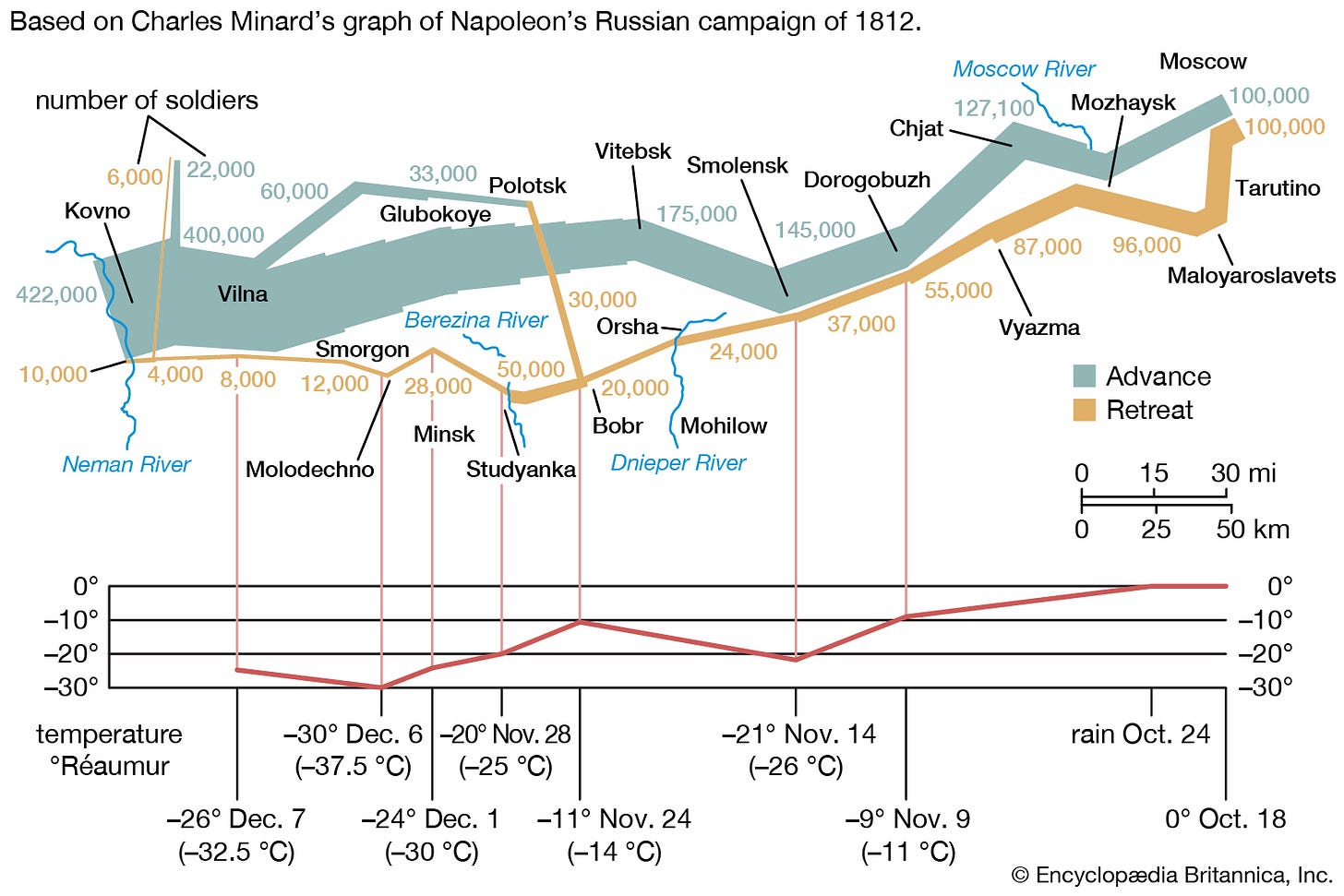

What came next has become the subject of popular legend: Napoleon gathered a massive army, began a doomed and foolhardy invasion of Russia, and lost his army in a retreat through the brutal Russian winter. This narrative of Napoleon’s campaign commonly casts him as some insatiable megalomaniac, someone who couldn’t resist drawing the sword even against an enemy as formidable as Russia and paid the price for a poorly planned and arrogant campaign.

Today, on the 209th anniversary of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, I’m here to tell you that the aforementioned narrative is wrong: The popular conception of Napoleon’s campaign as doomed to calamity at the hands of the Russian winter is highly misleading and needs revising. In this post, I’ll seek to combine a history of the campaign itself with a refutation of Napoleon’s overeager critics; in doing so, I hope to do justice to one of the turning points in European, and indeed global, history.

A Strategic Perspective

Something that gets overlooked in discussions of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia is the fact that it wasn’t strictly a French invasion. That is, the Franco-Russian war was really more of a war between France, Napoleonic Germany, and Napoleonic Poland on one hand, and Russia on the other. This is reflected in the composition of Napoleon’s Grande Armée of 614,000 soldiers, only 60 percent of whom were French. The rest consisted of 90,000 Poles and 150,000 Germans, with the German states of Baden, Bavaria, Wurttemberg, Westphalia, and Saxony all contributing contingents of upwards of 20,000 men. Indeed, even Prussia and Austria, Napoleon’s erstwhile enemies, were nominally his allies and supplied soldiers for the invasion.

Overall, in 1812, Napoleon ruled over 50 million people dispersed throughout Europe; Tsar Alexander, in contrast, ruled over 54 million people and a far less economically developed country. Thus, when Napoleon invaded Russia, it was far from clear that he would suffer defeat, let alone the calamity that befell him. When looked at as a war between most of Europe and Russia, rather than France and Russia, the Franco-Russian war appears a finely balanced one; it is only the benefit of hindsight that makes the invasion seem a doomed one.

The Invasion

Soldiers, the second Polish war is begun. The first terminated at Friedland; and at Tilsit Russia vowed an eternal alliance with France, and war with the English. She now breaks her vows, and refuses to give any explanation of her strange conduct until the French eagles have repassed the Rhine, and left our allies at her mercy. Russia is hurried away by a fatality: her destinies will be fulfilled. Does she think us degenerated? Are we no more the soldiers who fought at Austerlitz? She places us between dishonour and war — our choice cannot be difficult. Let us then march forward; let us cross the Niemen and carry the war into her country. This second Polish war will be as glorious for the French arms as the first has been; but the peace we shall conclude shall carry with it its own guarantee, and will terminate the fatal influence which Russia for fifty years past has exercised in Europe.— Napoleon’s bulletin to the Grande Armée, June 22, 1812.

Napoleon had no illusions as to how difficult the coming war would be: “I am about to embark on the greatest and most difficult enterprise I’ve ever attempted,” he had said to the Parisian chief of police in May of 1812. However, there was reason to be hopeful. Facing him were “only” 250,000 men spread across three armies led by Generals Barclay de Tolly, Prince Bagration, and Alexander Tormasov, respectively. Napoleon sought to prevent these three armies from uniting and use his nearly 2-to-1 numerical advantage to defeat each piecemeal.

At 5 a.m. on June 24, 1812, French soldiers began crossing the Niemen River into Russian territory. In a hint of what was to come, the sheer size of the army caused the crossing to take five days. It was the size of the French army that caused the Russians to adopt a defensive, scorched-earth strategy: Prince Bagration had wanted to launch a counter-offensive, but was dissuaded by the far more cautious Tolly and the reality on the ground.

In four days, Napoleon had entered Vilnius and chosen for his headquarters a mansion in which Emperor Alexander had lived only a few days earlier. However, to the South, poor generalship from his brother Jerôme allowed Bagration (and the Russian Second Army) to escape. Because of this failure, Jerôme resigned his command.

“If [movement] had been more rapid and better concerted between the Corps of the army,” French General Dumas later said, “the object would have been obtained and the success of the campaign decided at the very opening.” Although this is perhaps an overstatement, it is not beyond belief that had an entire Russian army—not least one led by Prince Bagration, the Russians’ most beloved commander—been annihilated in the opening weeks of the campaign, Napoleon’s position would have improved substantially (though it must be acknowledged that it was Napoleon’s decision to appoint the inexperienced Jerôme as commander that led to the debacle in the first place).

Nonetheless, only a week into the campaign, deficiencies in Napoleon’s plans were already becoming apparent. Not only was the decisive battle he had sought eluding him, but logistical problems were already beginning to mount. Summer thunderstorms made the bad roads in impoverished Eastern Europe worse: the French army had to make frequent stops to allow wagons from its supply depots in Warsaw, Königsberg, and Danzig to keep up. Unsurprisingly, this frustrated Napoleon’s pursuit of the evasive Russian army.

During this time, conditions in the army became dire. Baking sun made water a scarcity, and long marches in the summer heat caused soldiers to faint from exhaustion. Bottlenecks of wagons on the roads behind the Grande Armée even led to food shortages. Worse still, these conditions decimated the army’s horsepower: an average of 1000 horses a day died in Russia, not only depriving Napoleon of much-needed cavalry,4 but worsening supply problems (the draught horses used to move wagons perished alongside their counterparts in the cavalry).

“The rapidity of the forced marches, the shortage of harness and spare parts, the dearth of provisions, the want of care, all helped to kill the horses. The men, lacking everything to supply their own needs, were little inclined to pay heed to their horses, and watched them perish without regret, for their death meant the breakdown of the service on which the men were employed, and thus the end of their personal privations.” —Marquis de Caulaincourt, Napoleon’s master of horse.

The worst of the afflictions that befell the Grande Armée in the early stages of the campaign was an outbreak of typhus, something for which no army at the time had a response. The heat, water shortages, and cramped environment created the ideal environment for an outbreak: in the first week of the campaign, 6,000 men were infected each day. By July 21st, over 80,000 men had died or were sick, at least 50,000 of them from typhus.5 In Napoleon’s main army, a fifth of the men died within a month, largely from disease. All in all, in 1812, up to 140,000 of Napoleon’s soldiers died of disease. While these losses were not enough to derail the invasion, they—along with the aforementioned logistical nightmares already confronting the Grande Armée—significantly undermined Napoleon.

To March or Not to March

Disease and logistical problems notwithstanding, the Grande Armée marched deeper into Russia. On July 23rd, Russian General Barclay arrived at Vitebsk (nearly 200 miles east of Vilnius) and sought to make a stand against Napoleon. However, he was prevented from joining Bagration’s army by a French victory6 at the Battle of Saltanovka. Bagration’s failure to join Barclay forced the former to continue what was—contrary to popular belief—a retreat that was unpopular among the Russian army and population. Although this is conjecture, one wonders what would have happened if the Russians made a stand at Vitebsk: the battle there would surely have been a costly (perhaps even Borodino-like) one. Given that, it seems unlikely that the French army would have advanced as far into Russia as it ultimately did. Paradoxically, had Barclay’s plans not been foiled, Napoleon may ultimately have stood to benefit.

As it were, the Russians withdrew from Vitebsk. Napoleon, now 250 miles into Russia, stopped at Vitebsk for 16 days to reassess his options. Notably, despite not having fought a major battle, his main army was already at half strength. Upon entering Vitebsk, Napoleon remarked that “Here I must look around me; rally, refresh my army and reorganize Poland. The campaign of 1812 is finished; that of 1813 will do the rest.”7 Clearly, he seriously considered ending the year’s campaigning there: he was already much farther into Russia than he had planned and Vitebsk made for a good stronghold.

However, Napoleon ultimately decided to continue pursuing the Russian army. This was an entirely rational decision. First, in the previous month, he had advanced 190 miles and lost fewer than 10,000 men in battle: a pursuit thus seemed feasible both from a logistical and a military point-of-view. Secondly, it was still early in the year. Ending the campaign in July would have ceded the initiative to the Russians (not something Napoleon, a commander at his best on the offensive, was prone to do), and allowed them to train and deploy the 80,000-strong Moscow militia and a levy of 400,000 serfs. Finally, there was a belief among the French generals that Russia was not far from defeat. After all, large chunks of the country had been devastated and the army’s morale was dampened by constant retreats. It was thus perfectly rational to assume that the Russians would soon sue for peace: there was no way for the French to know that Emperor Alexander had said he’d “sooner let [his] beard grow to [his] waist and eat potatoes in Siberia” than make peace with the French.

“Why stop here for eight months when twenty days might suffice for us to reach our goal [Smolensk]? . . We have to strike promptly, otherwise everything will be compromised . . . In war, chance is half of everything. If we were always waiting for a favourable gathering of circumstances, we’d never finish anything. In summary, my campaign plan is a battle, and all my politics is success.” — Napoleon at Vitebsk, explaining his decision to march on Smolensk.

Given this, Napoleon decided to continue to Smolensk, one of the greatest cities of Old Russia and only 85 miles away. At Smolensk, he almost completed an encirclement of the Russian army: only heroic defending by the Russian 27th division and General Junot’s failure to carry out orders allowed the Russian army to slip away (albeit at the expense of a major city). On August 18th, Napoleon entered Smolensk. When he heard an anecdote about Russian soldiers singing “Te Deum” to celebrate their “victory,” he wryly remarked that “they lie to God as well as men.”8

At Smolensk, Napoleon held a rare council of war and consulted with his confidantes. Caulaincourt along with Marshals Berthier, Ney, Davout, and Murat were present. According to accounts, all but Davout and Murat were in favor of stopping at Smolensk. It was here where Napoleon really did make a mistake: he decided to march on Moscow. Years later, he would acknowledge that he “should have put [his] soldiers into barracks at Smolensk for the winter.” However, now only 230 miles from Moscow and perhaps emboldened by the Tsar’s decision to replace the cautious Barclay with Prince Mikhail Kutuzov,9 Napoleon decided to advance. He had not entirely incorrectly assumed that Kutuzov “has been summoned to command the army on condition that he fights”10 and couldn’t surrender the holy city of Moscow without a major battle. After this battle and the loss of Moscow, Napoleon posited, the Tsar would have to sue for peace.

“Before a month is out we shall be in Moscow. In six weeks we shall have peace.” —Napoleon at Smolensk, August 18th, 1812.

“In the twenty years that I have commanded French armies, I’ve never seen military administration to be so useless . . . the people who’ve been sent here have neither capability nor knowledge.” - Napoleon, September 3rd, 1812.

“The heat was excessive; I never experienced worse in Spain. This heat and dust make us extremely thirsty and water was scarce . . . I saw men lying on their bellies to drink horses’ urine in the gutter!” — Captain Girod de l’Ain, General Joseph Dessaix’s aide-de-camp, writing after a month without rain.

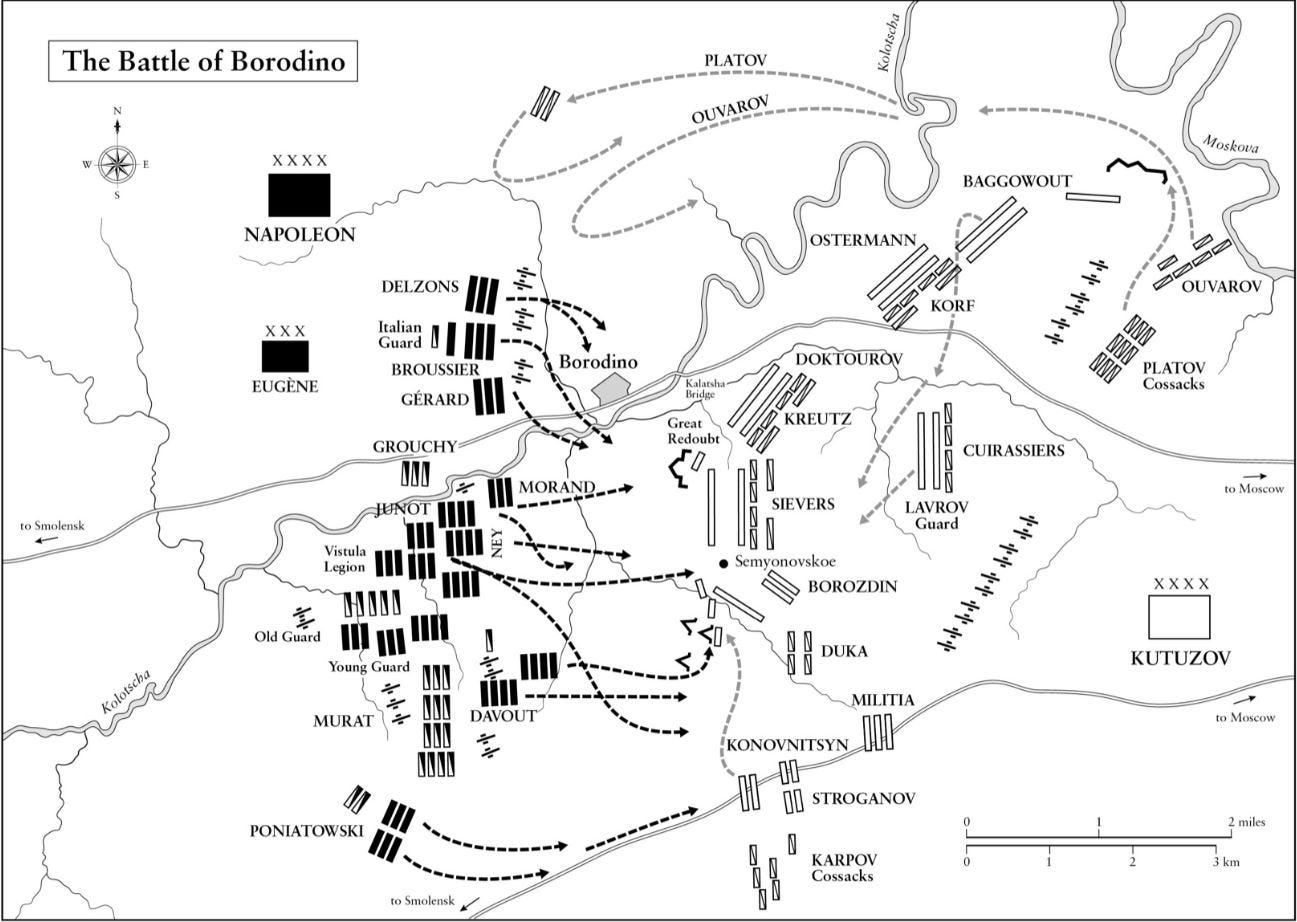

Borodino

As Napoleon predicted, the Russians refused to surrender Moscow without a fight. 65 miles to the west of Moscow, at a village called Borodino, Kutuzov fortified a position and sought to finally defeat Napoleon in open battle. Although I will not describe the battle in any depth here (for those more interested in tactical details, I recommend the following video), it is important to address two criticisms levied at Napoleon around it.

The first of these criticism concerns his allegedly unimaginative battle plan: the Battle of Borodino was largely a series of frontal assaults devoid of the intricate maneuvers of Napoleon’s earlier years. However, this was due more to the Russian position than anything else. Kutuzov wisely stationed his army between two rivers and built a series of fortifications to defend its front. With this in mind, it is difficult to imagine an alternative attack Napoleon could have mounted (barring a risky flanking maneuver of the kind suggested by Marshal Davout).

The second concerns his refusal to commit the Imperial Guard to the battle on two separate occasions. Those who levy this criticism assume that Napoleon’s famous Guard would have been able to turn the battle, which had at that point tipped in France’s favor, into a rout. In my view, this is far from clear, especially as committing the Guard would have opened his left flank and rear to General Platov’s cossacks. More generally, keeping the Guard in reserve was a rational move by a Napoleon disinclined to risk his last (and most loyal) soldiers in reserve nearly 2000 miles from Paris: “And if there should be another battle tomorrow, with what is my army to fight?” Napoleon famously asked the generals encouraging him to send in the Guard. Without the benefit of hindsight, that is a great question.

All in all, the Battle of Borodino had seen 103,000 French soldiers and 587 guns drive a Russian army of 120,800 men and 640 guns from a fortified position. The Russians had suffered around 43,000 casualties to Napoleon’s 28,000: their army was unable to fight another battle until it received significant reinforcements. Yet, unlike Napoleon, Kutuzov could receive reinforcements. That, along with the fact that Napoleon’s victory wasn’t decisive, served as a source of consolation for the Russians.

“I had never seen such carnage.” —General Rapp, wounded for the twenty-second time at Borodino.

“Peace lies in Moscow.” —Napoleon, September 8th, 1812.

Perhaps it was at Borodino where Napoleon’s last hope of victory slipped from his grasp: had he truly crushed Kutuzov’s army, rather than badly mauled it, peace might have been secured. Instead, Kutuzov lived to fight another day and the campaign continued. When, only a few days later, the Russians refused peace even after Napoleon’s occupation of Moscow and Kutuvoz’s army was bolstered by reinforcements, the balance of the campaign indelibly turned against Napoleon.

At Moscow’s Gates:

On September 15, 83 days after invading Russia and a week after his victory at Borodino, Napoleon entered Moscow. He expected to be greeted by a deputation of notables offering bread, salt, and the keys to the city, as was traditional. Instead, he learned that 90 percent of the city’s inhabitants had fled. Over the first two days of Napoleon’s occupation, Moscow burned. The fires had been started a day before on orders from the city’s governor, Count Fyodor Rostopchin: “I am setting fire to my mansion,” read a sign on his estate, “rather than let [sic] it be sullied by your presence.”11 To make sure the fires took their toll on the French (and the city), Rostopchin had also destroyed the city’s fire-engines before abandoning it; he had also released Moscow’s criminals from jail, giving them orders to keep the fire burning. Although the French rounded up and shot any of the arsonists they could catch (around 400 in all), without any fire-fighting equipment and lacking extensive knowledge of Moscow’s geography, they failed to contain the fire. As a result, more than two-thirds of the city burned; more than 12,000 people and 12,500 horses perished in the fire.

Two years later, Napoleon claimed that it was the fires that kept him from staying in Moscow. He rightly pointed out that the burning of Moscow was “an event on which [he] could not calculate, as there [was] not, [he] believe[d], a precedent for it in the history of the world.”12Napoleon had occupied Vienna, Berlin, and Madrid; nowhere had he encountered the nearly suicidal resistance he did in Russia.

Here, Napoleon made another mistake, albeit one only with the benefit of hindsight. Instead of immediately leaving Moscow, on September 18th, he decided to wait and see if Emperor Alexander would agree to end the war. His letters to Alexander went unanswered. In the meantime, Kutuzov, encamped not far from Moscow, received reinforcements: Napoleon was now outnumbered 110,000 to 100,000. It is unclear whether rumors also reached Napoleon that Austria and Prussia, his reluctant allies, were in secret talks with the Tsar. If indeed these rumors existed, they were true: Austrian foreign minister Metternich had promised the Tsar that Austria would not reinforce Austrian General Schwarzenberg’s corps. Although Napoleon had asked his wife, Marie Louise, to persuade her father (the Austrian emperor) to reinforce Schwarzenberg, no reinforcements were forthcoming.

It became clear to Napoleon that the army would have to leave Moscow and winter in Smolensk. Yet, perhaps expectantly waiting for a reply from the Tsar, he continued to put off his departure. This was not out of a lack of sagacity. Napoleon was keenly aware of the dangers of the upcoming Russian winter13 and his collection of charts and almanacs told him that freezing temperatures weren’t to be expected until November. “No information was neglected about that subject, no calculation, and all probabilities were reassuring,” wrote Fain, his secretary and a historian. “It’s usually only in December and January that the Russian winter is very rigorous. During November the thermometer doesn’t go much below six degrees [Celsius].”14 Napoleon believed this gave him plenty of time to return to Smolensk. After all, it had taken his army less than three weeks to get from Smolensk to Moscow (this included three days spent at Borodino).

On October 13th, the first (light) snow of the year fell. Five days later, the Grande Armée left Moscow in a 10-mile long column; along with it were 550 cannon and 40,000 wagons, many carrying loot. As Napoleon’s army left Moscow, its leaders did not yet know that the Russians were attacking the flanks of its 550-mile long route into Russia: the salient the French had created was narrowed by Admiral Chichagov’s advance from the South and General Wittgenstein’s advance from the North. In effect, including Kutuzov’s, three armies were converging on Napoleon.

Upon leaving Moscow, Napoleon hoped to return to Smolensk via a southern road going through Kalugula: this 275-mile route was slightly longer than the one he had taken to Moscow, but would also enable the Grande Armée to forage for supplies in unspoiled countryside. To prevent this, Kutuzov sent his army’s 6th Corps to block Napoleon’s route at a village named Maloyaroslavets. In the third-largest battle of the campaign, the French prevailed after bitter fighting. Yet, the battle clearly rattled Napoleon: like Borodino, it was costly and ultimately fruitless. The next morning, Napoleon—out trying to see if it was possible to advance through the Russian position on the road ahead—was nearly captured by a group of Russian cavalry (he was only saved by a cavalry charge led by General Rapp). From that day on, he began to wear a vial of poison around his neck.

Napoleon seems to have been shaken by the brutal fighting at Maloyaroslavets, which cost the French army eight generals: continuing down the Kaluga road would have led to another, similarly costly, battle. He vacillated over whether to continue along this road or return via the Moscow-Smolensk road the army had taken on the way to Moscow. While probably avoiding a major battle, this route would be longer and take the army through land bereft of supplies. Here, Napoleon convened arguably the most fateful council of war in his career.

“Smolensk was the goal,” wrote French historian Ségur. “Should they march thither by Kaluga, Medyn, or Mozhaisk?” That was the question posed to the council convened in a peasant’s hut in Gorodeya. Napoleon and Murat initially supported the Kaluga route; Davout, Eugène, Berthier, Caulaincourt and Bessières supported the Medyn route. Murat, however, harshly criticized this third route and argued that it would present the army’s flank to the Russians.

There is a dearth of information about the council and the reasons why Napoleon chose the route he ultimately did: the northern route back to Smolensk. Perhaps a shaken Napoleon wished to avoid fighting another Borodino along the Kaluga route and was reluctant to take the Medyn route due to the risks Marshal Murat identified. Napoleon seems to have felt that he had the time and supplies to take the longer route to Smolensk and return the way he came. Regardless of his rationale, Napoleon chose the ostensibly worst route. The historian Andrew Roberts has noted that “like a Shakespearian tragic hero, he chose the fatal path despite others being available.”15 Years later, Napoleon took responsibility for the decision: “I was the master, and mine was the fault,” he said.16

The Retreat:

“Those who were too weak to carry their weapons or knapsacks threw them away, and all looked like a crowd of gypsies.”—Private Jakob Walter, 7th Wurttemberg Regiment.

“The road was strewed with the dead: our sufferings exceeded imagination.”—General Rapp.

As the Grande Armée continued to retreat, Kutuzov’s army began marching alongside, attacking when the opportunity arose yet denying Napoleon the ability to counter. On October 27th, the Grande Armée marched past the old battlefield at Borodino, an unnerving sight where dogs and crows gnawed at unburied corpses. The Grande Armée even encountered one of its own: a French soldier who had had his legs broken and had spent two months living off of herbs, roots, and bits of bread in the pockets of corpses, sleeping in the bellies of dead horses. The effect of this encounter on the Grande Armée’s morale is not difficult to ascertain. Only a few days later, the Russians took nearly 3000 prisoners while attacking the French rearguard at Vyazma: the conspicuously large number of prisoners taken shows how close the French were to demoralization.

On October 29th, the temperature plunged to four degrees below zero. The army’s discipline began to break down: the sick and wounded, whom Napoleon had ordered loaded on carts, were pushed off by drivers seeking their own survival. The first heavy snow of the year came on November 4th; the following night, temperatures plunged to twenty below zero. The army’s attrition became severe: “Many, suffering far more from the extreme cold than from hunger, abandoned their accouterments,” army engineer Eugène Labaume recalled, “and lay down beside a large fire they had lighted, but when the time came for departing these poor wretches had not the strength to get up, and preferred to fall into the hands of the enemy17 rather than to continue the march.”18

Under these conditions, the army essentially disintegrated. By the second week of November, Labaume observed, “the army utterly lost its morale and its military organization. Soldiers no longer obeyed their officers; officers paid no regard to their generals; shattered regiments marched as best they could. Searching for food, they dispersed over the plain, burning and sacking everything in their way . . . Tormented by hunger, they rushed on every horse as soon as it fell, and like famished wolves fought for the pieces.”19

On November 7th, the temperature dropped to thirty degrees below zero; blizzards slowed the retreat to a crawl. Conditions in the army became truly dire and morale collapsed. Soldiers charged each other a gold Louis to sit by a fire, refused to share any food or water, ate the army horses’ forage, and drove wagons over men who had slipped in front of them.20 Only three weeks after leaving Moscow, a third of the Grande Armée was captured or dead; half of the rest were stragglers. Napoleon was reduced to a third of his fighting strength.

Two days later, Napoleon reached Smolensk. The first soldiers in, famished and exhausted, ransacked the supply depots and left nothing for those who followed (Marshal Ney’s rearguard arrived six days later). Napoleon, having hoped he could winter at Smolensk, realized that the state of the army and the lack of supplies meant the retreat had to continue. The retreat was doomed to become even more desperate, not least because the five days Napoleon spent at Smolensk allowed Kutuvoz to prepare an ambush at Krasnoi.

Napoleon left Smolensk seeking a bridge over the Berezina River, the nearest of which was 160 miles away at Borisov. Between November 14th and 18th, the remnants of the Grande Armée desperately sought to smash through Kutuzov’s army, which had blocked the path to Borisov, losing 39,000 men and 123 guns in the process. At the apogee of the fighting at Krasnoi, two whole regiments of the Young Guard21 were sacrificed to hold the road for the rest of the army. Having spiked 112 guns at Smolensk, Napoleon's army was also now effectively without artillery or cavalry. By rights, Krasnoi ought to have been the end of the Grande Armée. Kutuzov outnumbered it nearly two to one but failed to deliver the coup de grâce many argued he should have: he held units in reserve and was lambasted for his caution. Perhaps Kutuzov was dissuaded from a more aggressive approach by his army’s own terrible suffering. Having left Tarutino (near Malayaroslavets) with 105,000 men, after Krasnoi, Kutuzov found himself with only 60,000. While his losses were significant, they were not severe enough to prevent him from continuing to harass Napoleon.

“This is beginning to be very serious.” —Napoleon to General Caulaincourt, November 23rd.

The End:

Although Napoleon had escaped annihilation at Krasnoi, he now found himself in another debacle: three armies, outnumbering him nearly three to one, were closing in on him from three directions. Kutuzov raced westward with 60,000 survivors from Krasnoi, Wittgenstein marched south with 30,000, and Chichagov marched North with 34,000. Napoleon had been heading for Minsk, seeking the food and supplies his army so desperately needed. Now, he learned that, on November 21st, Minsk had fallen to Chichagov. The Admiral had then captured Borisov and its bridge over the Berezina river. Compounding Napoleon’s misfortune was the fact that a sudden thaw had unfrozen the river: the bridge Chichagov controlled was the only one for miles in either direction. Chichagov then burned the bridge after being forced out of Borisov by Marshal Oudinot’s second corps. Here, Napoleon’s army seemed truly doomed.

Miraculously, Polish soldiers found a ford across the river at Studienka, a village 8 miles away. South of Borisov, Napoleon ordered engineers to fake the construction of bridges, hoping to deceive Chichagov as to his real crossing site. In the meantime, engineers at Studienka worked tirelessly to build pontoon bridges across the river and possibly give the Grande Armée a chance of escape.

“Our situation is unparalleled. If Napoleon extricates himself today, he must have the devil in him.”—Marshal Ney to General Rapp, November 28th.

“The men went into the water up to their shoulders, displaying superb courage. Some dropped dead and disappeared with the current.” —Unknown Observer, Berezina crossing.

At 5 p.m. on November 25th, in temperatures that plunged to 33 degrees below zero, Dutch engineers began building two 300-foot pontoon bridges. They worked throughout the night, on occasion chest-deep in freezing water: although both bridges were completed in less than a day, few of the army’s engineers survived. Of the four hundred whose valiant efforts saved the army, only fifty ever saw home again.

Fortunately for Napoleon, Chichagov had fallen for Napoleon’s diversion; the Grande Armée was able to begin the crossing. As there were only two rickety bridges available, crossing priority was given to formed soldiers in fighting condition. In the meantime, this left the army’s crowd of stragglers on the wrong side of the river.

Yet, not every intact French unit made it across. For example, General Partonneux’s 12th division of 4,000 soldiers, which had been serving as the Grande Armée’s rearguard, was caught in a blizzard and blindly marched into a Russian army—the entire division was killed or captured. The next morning, two Russian armies under Wittgenstein and Chichagov attacked the French on both sides of the river. In desperate fighting and at great cost, the French managed to hold off the Russians until dark, at which point the entire army was able to cross the river.

However, the army’s stragglers were not so fortunate. Although, for two nights, officers had sought to get the stragglers to cross the bridges while they were not being used, in temperatures thirty degrees below zero, most had preferred to stay huddled around their fires. Thus, on the morning of the 29th, with the French army having left and the Russians approaching, hoards of stragglers surged in panic toward the bridges. In the process, many were crushed underfoot while others fell into the freezing river; those that tried to swim met an inevitable death. At 9 a.m., in order to prevent a Russian pursuit, French engineers burned the bridges, cutting off thousands of stragglers: while some became Russian prisoners, others were simply killed by the advancing Cossacks.

“What appalling misery … What a multitude have perished in this retreat.”—Captain Franz Roeder, Lifeguards of the Grand Duke of Hesse.

As the remains of the Grande Armée marched to Vilnius, the weather worsened as temperatures plummeted to 37 degrees below zero. In these conditions, the Russian army decided against a pursuit. On December 9th, 51 days after the start of the retreat, the surviving 20,000 men of the Grande Armée crossed the Niemen River into friendly territory. Four days earlier, Napoleon had left the army,22 traveling to Paris to address the political and diplomatic consequences of his defeat. He arrived there in 13 days and quickly began recruiting another army. While his invasion of Russia was over, his military career certainly was not.

“Fortune has dazzled me, gentlemen. I’ve led it lead me astray. Instead of following my plan, I went to Moscow.I thought I would make peace there. I stayed too long. I’ve made a grave mistake, but I’ll have the means to repair it.” —Napoleon to his ministers upon his return to Paris.

Conclusion

All in all, the invasion of Russia had cost Napoleon’s empire 524,000 men. Out of every 12 men who marched into Russia with the Grande Armée, one died in battle or through wounds sustained in combat, two were taken prisoner (out of these two, one died in captivity), seven died from disease or the effects of climate, and two returned. The Grande Armée, the largest army Europe had ever seen, had been reduced to a husk of its former self. After a 43-day and 500-mile retreat, with 23 days spend in sub-zero temperatures, it could count on only 10,000 combat-ready men. By the time the Grande Armée crossed the Niemen, many of its units were at just 5 percent of their strength. Marshal Davout’s corps of 66,000 now numbered 2,200; of Oudinot’s corps of nearly 48,000, only 4,653 survived; and the Imperial Guard of 51,000 now contained only 2,000 men.23

While it is often forgotten, the Russian army also suffered immensely throughout the campaign. In 1812, nearly 150,000 Russian soldiers were killed, 300,000 were wounded or frostbitten, and countless civilians perished as large swathes of Russia were ruined. The Russian army now consisted of only 100,000 men.

Although, in the following years, Napoleon had opportunities to save his empire, his army never really recovered from the Russia campaign. It had not only lost its best soldiers, but also countless horses in an unparalleled equinocide: for the rest of the Napoleonic wars, the Grande Armée’s cavalry was a shadow of its former self. For example, in the 151,000-strong army Napoleon mustered for the next campaign, there were only 8,540 cavalry to face the 30,000 cavalry of his opponents.

After his defeat in Russia, Napoleon’s erstwhile allies24 (Prussia and Austria) turned against him: in the war that was to follow, he would face a newly emboldened and immensely powerful coalition that his weakened army proved incapable of matching. Thus, the Russia campaign was effectively the turning point of the Napoleonic wars and deserves every bit of the attention it receives.

The Takeaway

The goal of this post was to give a history of the Russia campaign that addresses some of the issues with the popular narrative surrounding Napoleon’s invasion. We have seen that:

The campaign’s outcome was far from a foregone conclusion: The Russians could have been defeated in the early weeks of the campaign (especially if Jerôme and General Junot had not blundered). Alternatively, they could have been decisively defeated at Borodino. It was only once the Grande Armée found itself in an uninhabitable Moscow, outnumbered and 500 miles away from friendly territory, that the balance of the war shifted away from it.

The Russian’s famous scorched-earth tactics were ad hoc and risky: At the beginning of the campaign, Prince Bagration and other aristocratic Russian generals had wanted to stand and fight. It was only the sheer size of the Grande Armée that dissuaded them from doing so. Even once adopting this strategy, the Russian army needed to stand and fight (and thus risk defeat) on multiple occasions to avoid demoralizing the nation and its soldiers. Additionally, as we’ve established, this strategy was far from a guarantee of victory.

The Russian winter did not defeat Napoleon: Contrary to popular belief, more soldiers perished in the summer advance to Moscow than in the winter retreat from it. Heat, typhus, and dysentery caused far more damage to the Grande Armée than did the Russian winter. That being said, the Russian winter was undoubtedly brutal and was arguably the Grande Armée’s coup de grâce. However, it is also important to note that, by rights, the Grande Armée ought to have avoided the winter. It was the early arrival of severe temperatures, Kutuzov’s delaying actions, and Napoleon’s fateful choice of route that condemned the Grande Armée to a march in deadly winter temperatures.

The Grande Armée deserves more credit: It ought to be remembered that, in the span of a few months, the Grande Armée managed to fight its way 500 miles into the joint-most powerful nation in Europe, conquer vast swathes of its territory, and occupy its economic and cultural capital. It marched at an incredible pace: the Grande Armée marched from Poland to Moscow and back in the same time it took the Wehrmacht to get to Moscow nearly 130 years later. The Grande Armée’s defeat was due less to Russian military acumen (it was only when the Grande Armée began its retreat that the Russians started to win battles) than to outbreaks of disease, logistical failures caused by Russia’s impoverished countryside and poor roads, and brutal climatic conditions.

The Importance of Political Will: As has been mentioned, in discussions of Napoleon’s 1812 campaign, Russia’s immense losses often get overlooked. Indeed, it is not difficult to imagine a less determined Tsar signing a peace treaty with Napoleon, who, even early in the campaign, had offered relatively generous terms. Instead, Tsar Alexander decided that he would defeat Napoleon at any price, declared him the antichrist to inspire a guerilla war against him, and waged an arguably irrational war of annihilation against the Grande Armée. He succeeded, but only with losses that most other monarchs would have gawked at.25 Napoleon could not have imagined how tenaciously the Tsar would resist the invasion. Even upon reaching Moscow, he sued for peace, fully expecting to get it: there was simply no way he could have known that his former ally from Tilsit was now an irreconcilable, kamikaze-like enemy. Napoleon’s failure to appreciate how stubborn Russian resistance would be was an important factor in his eventual defeat.

Acknowledgments:

In the course of writing this post, I consulted an eclectic set of sources about Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, most of which are cited below. I would also be glad to share the source of any figure within the post that is not already cited. Special thanks goes to Andrew Roberts for his biography of Napoleon, the YouTube channel Epic History TV for its incredibly well-researched content, and Jonathan Schneiderman and Will Foster for their editing.

The Russians feared that this was a step toward the creation of an independent Polish state.

Although minor, this Duchy was ruled by Alexander’s sister’s father-in-law; the annexation also violated the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit.

Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon: A Life. New York, New York: Viking, 2014. Print.

Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon: A Life, 588.

The French army at Saltanovka was led by Marshal Davout, widely considered the ablest of Napoleon’s marshals.

Summerville, Napoleon’s Expedition to Russia, 284.

Summerville, Napoleon’s Expedition to Russia, 67.

Kutuzov was defeated by Napoleon numerous times before, most notably at Austerlitz.

Summerville, Napoleon’s Expedition to Russia, 67.

Merridale, Red Fortress, 211.

Ebrington, Memorandum, 12.

To those of you interested in military history, while in Moscow, Napoleon read Voltaire’s History of Charles XII: he was keenly familiar with the fate the Swedes had suffered at the hands of the Russian army and winter.

Fain, Manuscrit de 1812 II, 151-2.

Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon: A Life, 551.

Labaume, Crime of 1812, 189.

Men such as these did not fare much better than their still-marching counterparts. In one column of 3,400 French prisoners-of-war, only 400 survived; in another only 16 out of 800 did so.

Labaume, Crime of 1812, 186.

Ibid.

Brett-James, Eyewitness Accounts, 233-239.

Just as the Old Guard were the best of Napoleon’s veterans, the Young Guard was a regiment composed of the most promising of the army’s conscripts.

By this point, it was only two days’ March from Vilnius and safety.

Labaume, Crime of 1812, 233.

Having been humiliated by Napoleon, their loyalty was always dubious.

Both Prussian King Frederick William III and Austrian Emperor Francis II signed punitive peace treaties with Napoleon: neither had suffered the immense losses Alexander had in 1812.